Senza di lei non esisterebbe l’alveare. Non ci sarebbero il miele, il polline e la pappa reale. In definitiva, non ci sarebbero le api, non nella forma in cui le conosciamo.

Lei è l’ape regina, fondamento di ogni famiglia, unica ape feconda, capace di deporre quantità impressionanti di uova per garantire la sopravvivenza della sua stirpe e, all’occorrenza, spostare le colonie verso una nuova casa.

Seguiteci e scoprite tutti i segreti della regina, l’ape più importante dell’alveare.

Come nasce una Regina?

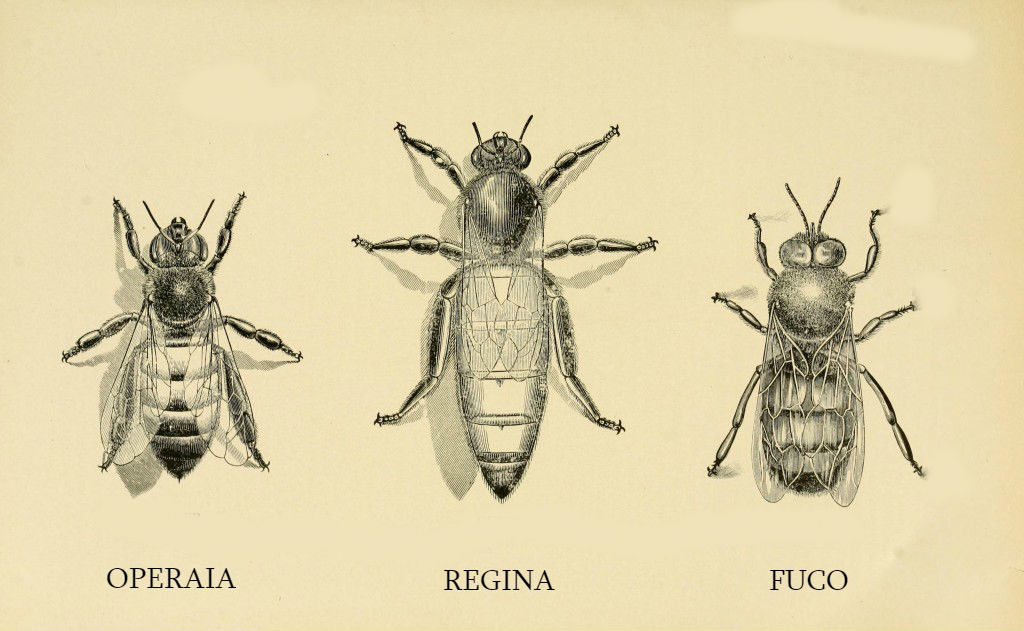

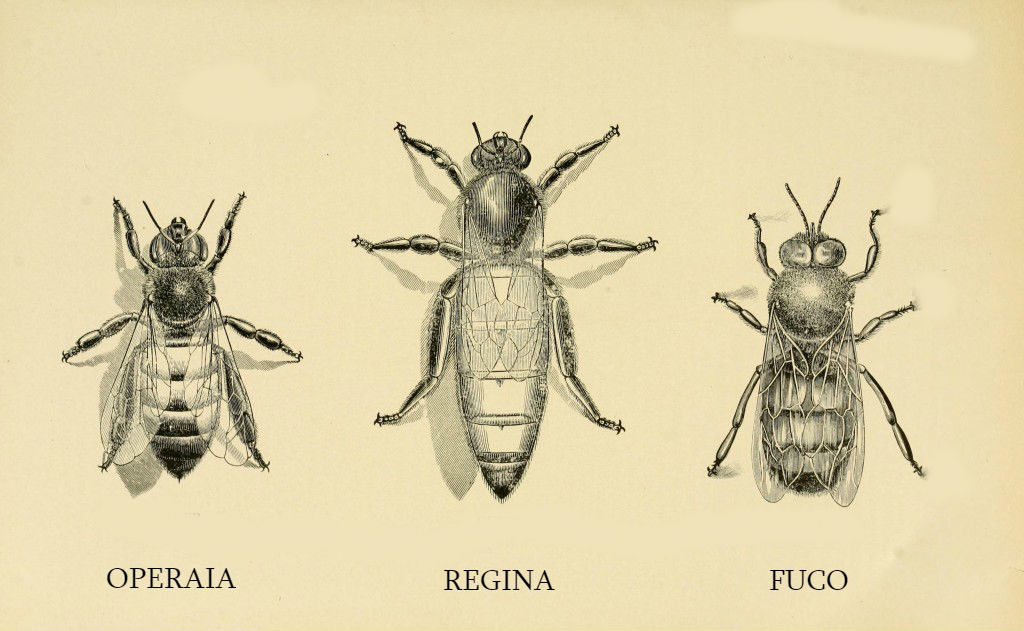

La regina è l’ape più grande, la più longeva è l’unica feconda, capace cioè di generare una nuova colonia, o «famiglia». Queste differenze sono il frutto di un’alimentazione speciale. Dopo la deposizione dell’uovo, le operarie svezzano le larve reali per circa 15 giorni con la pappa reale, che sarà l’unico alimento della regina per tutta la vita. Dopo questo periodo la regina può uscire dalla sua cella, anch’essa speciale: non è infatti posta in orizzontale, ma in verticale e ha le fattezze di un’arachide.

La lotta per il trono

Una colonia può allevare fino a 30 «principesse», dette «regine vergini». Quando le api percepiscono che la reggente non è più in grado di svolgere il suo ruolo, devono assicurare la la sopravvivenza della colonia. Costruiscono allora le celle reali per far nascere una nuove regine. Quando le «regine vergini» si schiudono, ciascuna compete per il proprio regno fino a che ne rimane in vita una sola. A volte accade che una vergine, nata prima delle altre, uccida le “sorelle” mentre sono ancora nella loro cella. Se più vergini vengono alla luce contemporaneamente, tutte meno una abbandonano l’alveare seguite da un gruppo di “fedelissime” (sciamatura). Accade questo perché nell’alveare può rimanere una sola regina.

Il canto della regina

Nel momento in cui vengono alla luce (o addirittura mentre sono ancora nella loro cella reale), le «regine vergini» cominciano a emettere un particolare stridìo, simile al suono di una trombetta. È il «canto della regina» e si pensa abbia diversi scopi.

- È un «peana di guerra» per mettere sull’attenti tutte le pretendenti al trono e cominciare la lotta per il sopravvento.

- È un «orazione politica» per procacciarsi i consensi delle api della colonia, al fine di farsi eleggere nuova regina.

- È una «serenata» per i fuchi – ovvero i maschi delle api – per farsi seguire, fecondare e dare origine ad una nuova famiglia.

- È un segnale di partenza, che la regina vergine in procinto di sciamare emette per ritardare la nascita di altre vergini (in questo caso le operaie inibiscono le altre vergini nelle loro celle, aggiungendo strati di cera per impedirne la fuoriuscita)

Potere al popolo

Per quanto l’ape regina sia in grado di influenzare il comportamento delle sue operaie grazie alla produzione di feromoni, l’alveare è un super-organismo, ovvero una forma di collettività in cui le decisioni sono prese attraverso una specie di maggioranza “senziente”. Quando questa maggioranza percepisce la fine di una regina, fa di tutto per agevolare un cambio al vertice deponendo uova nelle celle reali. Caso limite è la sciamatura in cui le operaie agiscono “democraticamente”: si crede infatti che singolarmente o a piccoli gruppi possano decidere di seguire la vecchia regina pronta al distacco, o restare con la nuova che garantirà la sopravvivenza della famiglia.

Nutrice e assassina

Al contrario di quello delle operaie, dentellato e irregolare, il pungiglione della regina è liscio. Il suo scopo è duplice: quando è gravida, la regina lo utilizza per deporre le uova, come fosse una pipetta; in caso di combattimento, invece, il pungiglione diventa un affilato stiletto, pronto a trafiggere le rivali.

Il volo nuziale

Una regina può deporre fino a 2 mila uova al giorno, 250 mila l’anno per un massimo di 5 anni di vita. Per poterle fecondare accumula il seme dei fuchi all’interno del suo addome, rilasciandolo gradualmente. L’accoppiamento non può certo essere quotidiano, ma avviene una sola volta, nel periodo del volo nuziale. La regina vergine si solleva in aria seguita dalla «cometa di fuchi», un nugolo composto da un centinaio di maschi. L’accoppiamento multiplo fornirà alla regina il materiale genetico per gli anni a venire fino a che, esauritosi, darà vita a uova non fecondate, che produrranno solo api maschio. È la cosiddetta «regina fucaiola» che, se individuata dalle operaie, verrà prontamente sostituita.

Nutrita e riverita

L’unico scopo della regina è continuare la specie. Non deve preoccuparsi di nulla: viene seguita da uno sciame di ancelle che la puliscono, la nutrono e la difendono, assistendola in ogni esigenza. Ma la regina è gelosissima del suo ruolo: mentre le api operaie la riveriscono, lei rilascia il feromone reale, un potente inibitore degli organi sessuali che ha la funzione di renderle sterili.

[:en]

[:en]

Without the Queen Bee, a hive would not exist. There would be no honey, pollen or royal jelly. There wouldn’t even be bees, at least not as we know them.

She reigns supreme, the foundation of the hive and the head of the family, the true queen bee. She lays large quantities of eggs to ensure the hive’s continued survival and will force the colony to migrate if necessary. The hive revolves around her.

We have seven secrets of the queen bee, the most important bee in any hive.

How is the Queen born?

The queen is the largest bee in the hive, the one who lives the longest and is the sole reproducer in a hive, all thanks to a special diet. After the queen lays her eggs, of which some will be unfertilized and become male drones and others will be fertilized and either become workers or virgin queens dependent on diet, the worker bees feed all the royal larvae a diet of only royal jelly for 15 days. Royal jelly is the only thing a Queen Bee eats throughout her life. After this period, the queen emerges from her cell, which is itself unique to the regular hexagonal shape. It lays horizontally in the shape of a peanut.

The struggle for the throne

A hive can breed up to 30 ‘princess’ bees, which are truly called virgin queens in order to ensure their survival. In fact, when worker bees sense that their current queen can no longer lay eggs, they will begin building up royal cells and feeding more fertilized larvae to ensure the birth of a new queen. When more than one virgin queen is hatched, they will fight to the death. The winning virgin queen will ensure her dominance by destroying any other royal cells that may still be unhatched. If a hive becomes too large, the old queen will leave with a ‘swarm’ of faithful workers and half the hives reserves to create a new colony.

The queen’s song

When the virgin queens emerge from their cells (and even sometimes when they are near emerging), they begin emitting a high-pitched buzzing called piping that sounds similar to a trumpet. It is the “queen’s song” and is thought to have a few different purposes:

- A “war call” that signals their location so that all ‘pretenders to the throne’ may come and fight the queen,

- A “political campaign” to obtain the consensus of the worker bees to be regarded as their new queen,

- A “serenade” to the drone male bees so that they will find the queen for her nuptial flight,

- A “warning” that the virgin queen will leave on her nuptial flight and that the workers must prevent the emergence of other virgin queens by adding more layers of wax on top of their cells.

Power to the people

Although the queen is able to influence the behaviour of all the bees in the hive thanks through her pheromones, the hive functions as a type of ‘super-organism’ that thinks collectively. It is called eusocial and means that the bees make decisions for the collective of the hive through a kind of ‘sentient’ majority. When this majority senses the near-end of an old queen, they will do everything in their power to ensure their survival by feeding more larvae with royal jelly to create virgin queens. The only limitation on this group think is in the case of swarming. Worker bees will act ‘democratically’ and choose either individually or in small groups to leave with the old queen or remain with the new one to ensure the continued survival of the hive.

Nurse and assassin

Contrary to the workers, which have notched and irregular stings, the queen’s is smooth. This is for two reasons: when she is pregnant it functions as a pipette to lay eggs and when she is in combat, the sting is like a sharp knife, ready to pierce rivals.

The nuptial flight

A queen bee is capable of laying up to 2000 eggs a day, 250 000 per year, for a maximum of 5 years. To do this, she accumulates the semen from mating drones in her belly, only releasing it by choice when laying eggs. Mating does not occur daily. In fact, it only happens once in what is called the nuptial flight. When a virgin queen emerges, she will leave the hive followed by a swarm of drones (male bees) who will compete to mate with her in flight. She will mate with multiple drones, collecting enough genetic diversity from their semen to lay eggs throughout her lifetime. The queen can sense when worker or drone bees need to be laid and selectively chooses to fertilize (worker larvae) eggs or leave them unfertilized (drone larvae) when laying. The queen is the only bee that can truly reproduce in a hive. Rarely there are laying worker bees, that only produce drones, and if detected are promptly replaced in the hive.

Nourished and revered

The queen has a single purpose: to reproduce. She doesn’t even need to think about the basic necessities of survival. A small swarm of maiden bees follows her constantly, cleaning her and feeding her, nurturing her and defending her to the death. However, the queen is a jealous queen. She releases a royal pheromone that is a powerful inhibitor of the sexual organs in the worker bees in order to ensure their sterility.